A year after first speaking with several prominent Ukrainian journalists and writing about their experiences during Russia’s war against Ukraine, I reconnected with two of them, Angelina Kariakina and Nataliya Gumenyuk. We discussed how their lives have changed and what war-related stories global news outlets are failing to cover.

Kariakina and Gumenyuk both reflected on the intensifying daily deprivations, the exhaustion, the emotional toll of loss of life, and the widespread survivors’ guilt. The cost of survival is huge, but so too is their soaring hope for a better future, which is the social glue that binds Ukrainians together.

What partly frustrates this hope, however, are the gaps and biases in global news coverage of the war that Kariakina and Gumenyuk spot. My subsequent investigation exposes an interesting south-north divide in coverage lenses that demands further exploration.

(1) Provide missing context that audiences need to know

A few days ago, sitting in a restaurant with an educated, successful friend, we started talking about the war. Momentarily she slouched forward and whispered: “You know, I really don’t understand why this war started.”

Like most audiences globally, this friend lacks important background information about Russia’s invasion. This chimes with Kariakina’s analysis that global news media are omitting context, especially regarding Russia’s history of colonialism in Ukraine, from their coverage: “The war strategy is being covered,” she said. ”But there is a bigger contextual problem which is missed, that makes this war hard to stop: the threat of the death of Russia as an empire. The world doesn’t understand that Russia treats Ukraine like it is a Russian colony.”

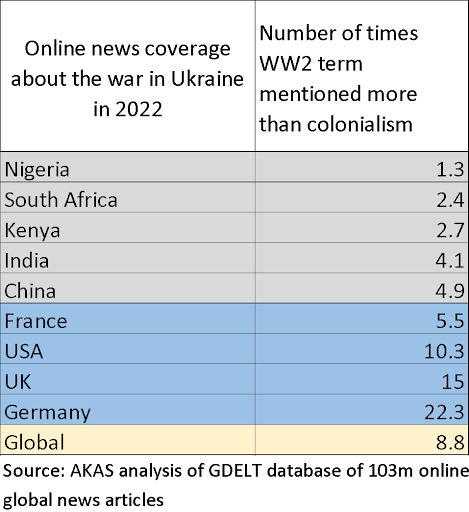

I checked this argument by commissioning AKAS to analyze news stories about the war on Ukraine published in 2022. Astonishingly, we found that World War II is mentioned nine times more frequently than colonialism. Moreover, there is a distinct south – north divide, with Global South news outlets more likely to use the colonialism frame than those in the north, who have almost entirely missed this angle. Perhaps Western countries’ blind spot about their own colonial pasts is preventing journalists from covering the colonialism angle in relation to this war effectively.

News providers covering the war in Ukraine owe it to their audiences to explain that early in the 20th century Ukraine was split between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires. Viewed in Moscow as “Little Russia’,” Ukraine had been attempting to gain independence in the years since but only managed to do so following the collapse of communism in August 1991. This left Russian nationalists feeling betrayed.

(2) Unpack prevalent social norms in Russia

It is important to shine a light on social norms in Russia that squash freedom of expression and support the war, while, crucially, encouraging Russians’ ignorance about their past which enables it. “Russia never deconstructed the 70 years of the Soviet Union. Russians never critically thought about their past,” said Kariakina.

This ignorance makes it easy to repeat the repressive past. Since coming to power in 2000, Putin has made a concerted effort to suppress and rewrite the Soviet past, explains Coda Story’s “Generation Gulag” report. With success, too: half of young Russians have not heard of the Great Terror, the Stalin-era purges.

In 2019, 70% of Russians approved of Stalin’s role in history. The deficit of truth about the gulags and other Soviet mass atrocities has been underpinned by a centuries-long lack of political and economic freedom. This acceptance of authoritarianism has powered Russia’s war against its former colony, Ukraine.

[Read more: A year after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, how have journalists been impacted?]

(3) Avoid narratives and language that create false equivalencies between the aggressor and the aggressed

Global coverage of Russia’s war on Ukraine often creates a false equivalency between the two sides, argued Gumenyuk. It frequently fails to reiterate that Ukraine “is a peaceful nation, a non-militaristic society that is forced to look for weapons to defend its sovereignty.”

The war is, in addition, referred to as a “conflict” in 36% of global coverage. This term perpetuates a false sense of equivalency between the two sides. It is more accurate to use descriptors that differentiate between the aggressor and the aggressed.

(4) Amplify more Ukrainian perspectives about the war

Kariakina raised a concern that Russians, including those who have fled the country, account for a disproportionately high share of voice in the war narrative; that their share of voice may be similar or higher than that of Ukrainians on international panels.

Working on a story comparing Russian war tactics in three cities in Ukraine, Chechnya and Syria, Kariakina is struck by how similarly the Ukrainians and the Chechens assess the narratives constructed about Russia’s wars against their countries. With noticeable frustration she observed: “[Chechens] say that their voice was drowned out by the good Russian human rights activists, by the Russian journalists. It is they who told the Chechens’ war stories, not the Chechens themselves.”

We turned to GDELT analysis to juxtapose Russians’ and Ukrainians’ share of voice in news coverage. Once again, the results stunned me: in 2022, references to Putin were four times as common as references to Zelensky, and Russian experts were cited twice as frequently as Ukrainian experts.

When it comes to understanding the war in Ukraine there is a need to tilt the share of voice toward those on the ground. Journalists must be careful not to treat the voices of Russian emigrants as interchangeable with those of Ukrainians; their perspectives are very different, despite also considering Putin an enemy.

I realize once more how critical context is to understanding the war in Ukraine, and how scarce it is in today’s news coverage. I also appreciate the value of applying a multi-country lens when analyzing Russia’s recent wars, and the importance of drawing parallels between Russian and other Western countries’ colonialism prior to the 20th century.

Without this context, there is a real danger that global audiences dissociate from any moral judgement of who is right and who is wrong in this war. This apathy is what Putin’s Russia is banking on.