The global supply of green hydrogen is likely to be unstable and subject to disruption. Strategic hydrogen reserves will be required by future importers, such as China, Europe, and the United States. They will also need to coordinate their use to these reserves to ensure a smooth supply, says Nick Crawford in the third article in a series on the role hydrogen plays in future energy strategy.

Countries around the globe are committing to using green hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels in order to achieve net zero carbon dioxide emissions. Green hydrogen is a viable alternative to fossil fuels in shipping, aviation, haulage and steel, cement, and fertiliser industries.

These industries will require a steady supply of green hydrogen and much more Imports will ensure supply It is more affordable to produce it in countries that have abundant solar and wind power. However, despite the abundance of renewable resources, the availability and cost of solar and wind energy varies greatly from one month to the next and year to the next. Political instability and disputes can also disrupt the supply of hydrogen, as can other energy supplies.

The The market for green hydrogen is tight Therefore, it is crucial to invest in hydrogen storage and build up strategic and seasonal reserves for supply security. Some states will depend on others to store their reserves. International coordination will be required to manage large swings in global supply.

Variable supply

Like natural gas, green hydrogen will also be subject to large price swings. This will not happen due to fluctuations in demand, unlike natural gas. Natural gas is used to heat homes, so it is more in demand when the weather is cold. It is also used to produce electricity so it increases in demand when other sources, such as renewables are low. However, hydrogen-based fuels and hydrogen will be used most frequently in industry and transport, which have a higher demand. Japan and only a few other countries plan to use hydrogen at large for domestic heating and electricity.

The main driver of price swings for green hydrogen will be the fluctuating supply. Natural-gas production is steady and consistent. However, there are four major factors that make green-hydrogen production unstable and susceptible to disruption.

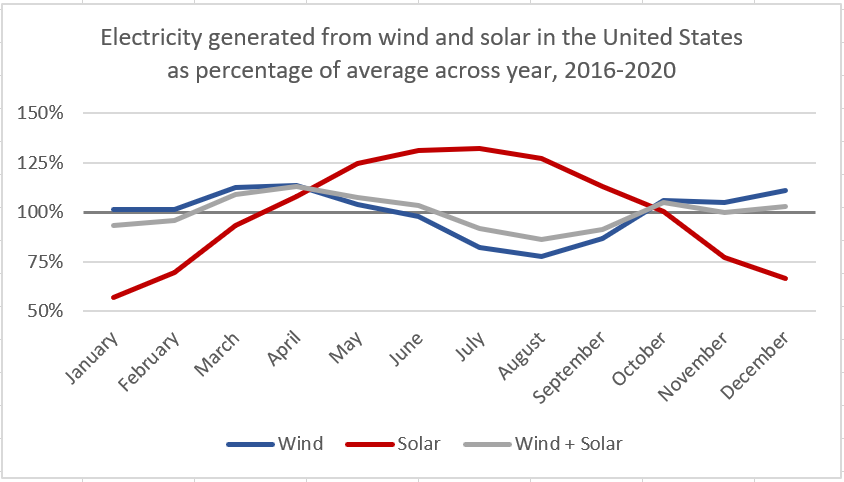

Seasonal variability is the first. Because green hydrogen is dependent on renewable electricity, production will vary according to the amount of sunlight and wind. These seasonal swings can be quite dramatic. The chart shows that there was a significant difference in the best and worst months to generate electricity from solar and wind in the United States, between 2016 and 2020. This was despite the fact that the USA is a country with continental proportions and a wide variety of weather patterns, which tend to partially compensate each other throughout the year. Even smaller countries may experience greater seasonal variability.

Notice: Author calculations are based on data provided by the US Energy Information Administration. They do not account for any changes in solar and wind capacity during each year.

Inter-annual variability is the second factor. This refers to fluctuations in electricity generation from renewables caused by weather changes and maintenance. The standard deviation of wind farms from the average year is approximately 6%. However, there are some countries that are not. More frequent swings Some years will see production swings that exceed 6%. There is not much data available on the inter-annual and seasonal variability of solar and wind power in many countries that are expected to be major green hydrogen exporters.

Third, natural events can cause temporary disruptions in hydrogen production, such as earthquakes, volcanic-ash clouds and sandstorms. Drops in hydrogen supply could result from events that either stop or reduce the output of renewables and hydrogen facilities.

Fourth, there is the possibility of man-made disruptions to hydrogen supply. The energy industry is constantly concerned about political instability and attacks against critical infrastructure in producing countries. These risks also affect the production of hydrogen. Manipulation is another concern. Exporter countries will be able to use their bargaining power to pressure importer countries into withholding hydrogen supplies. This is similar to what OPEC did in 1973 when it placed an embargo on oil exports from Western countries that had supported Israel in the War.

Mitigation measures

Transport and heavy industry will increasingly depend on hydrogen-based or hydrogen-based fuels. The knock-on effects from disruptions in hydrogen supply will be more severe. This could affect, for instance, goods movement locally as well as globally.

One way to reduce the volatility and disruptions in hydrogen supply is for importer nations to purchase green hydrogen from different countries and regions. This is only a small part of the solution. Even if one exporter is short, global hydrogen prices would rise. With a tight spot market . Price swings can be quite dramatic due to inelastic demand and supply. The shortfall cannot be made up by green-hydrogen producers, and users are unable to switch fuels easily.

Hydrogen produced from natural gas by steam methane reforming could up to a certain point compensate for seasonal, inter-annual, or random shortages in green-hydrogen supplies. This will depend on the amount of investment made in SMR plants over the next years (with or without carbon storage and capture to make ‘blue hydrogen). Instead, some governments support green-hydrogen investments only.

To mitigate fluctuations in supply, it is important to invest in hydrogen storage and hydrogen-based fuels. The ability to store seasonal hydrogen reserves will help smooth out variability in production. Building up strategic reserves would also help to prevent unexpected disruptions or larger price swings.

Since 1973, the OPEC oil embargo, maintaining strategic oil reserves has been a key component of Western countries’ energy-security policies. In 1974, the International Energy Agency was established. It required member states that were net importers to have 90 days worth of oil imports. This norm has been adopted by other countries, including China. These reserves were put into effect in November 2021 when the United States, China, India and South Korea coordinated releases from their strategic reserve to lower rising oil prices.

Although hydrogen will not be as important to the global economy as oil, it will still have the same impact on the economy. A greater variety in green-hydrogen supply means that governments will have to access hydrogen storage more often than they use their strategic oil reserves.

Hydrogen storage

There are many options for large-scale hydrogen storage, including gaseous hydrogen-based fuels like ammonia. However salt caverns have the best potential. Salt caverns have been used for many decades to store natural gas at large scales. The UK The US is the best place to store hydrogen on small scales. However, salt-cavern hydrogen storage has its own problems.

First, large-scale storage in salt caverns of fuel gases is costly. This means neither exporters nor industrial users are likely to pay it. The cost is usually borne by industrial users. The UK’s largest natural gas storage facility was closed in 2008 after the government decided to stop subsidizing it. Cavern storage might be a good investment for hydrogen exporters. However, they won’t know until many years that the hydrogen and ammonia they hold back will be available to sell at a higher price.

Governments of importer nations will be responsible for developing storage facilities and building up strategic and seasonal hydrogen reserves. Because it is cheaper to store liquid-hydrogen-based fuels (such as e-kerosene) than hydrogen gas and gaseous hydrogen-based fuels, the industries that use these liquid fuels, such as aviation, will accumulate their own seasonal reserves. However, the importer governments will likely need to have strategic reserves of these liquidfuels, just like they did for oil.

Second, salt-cavern storage is not possible in all geological formations. While North America and Europe have large salt deposits that can be used to make caverns, there is not enough in East Asia, South America, and sub-Saharan Africa. Japan and South Korea are likely to adopt hydrogen fuels early. They have no salt deposits. Japan’s inability to store natural gas has made it difficult for them to have salt caverns. It holds 40% of its electricity despite relying on natural gas for 40%. Only two weeks of reserve .) China is short on salt deposits and will likely have a high demand for hydrogen once its massive steel and cement industries switch to the fuel.

Future importers like South Korea, Japan, and China will need to keep hydrogen reserves overseas. They will need to enter into agreements with other countries in order to build and maintain storage facilities and to allow for the release of reserves when necessary. Australia may be a possibility for South Korea and Japan. Which is likely to supply most of their hydrogen , and increase the cost of hydrogen storage at salt caverns. It is not clear where China will go for hydrogen storage.

Freeride or coordinate

In order to ensure a steady supply of hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels, international coordination will be more important as the hydrogen industry expands over the next 10-30 years. This will require a diverse group of net importers, including the US, China, Japan, the European Union, and Japan. They may have to work together in times of severe disruption to free up enough hydrogen reserves to maintain global supply. They will all want to avoid the problem of one country waiting for the other to release reserves and benefit from the increase in global supply at no cost.

These states might look to the IEA or the recent strategic petroleum reserve release as a model. Hydrogen presents a greater challenge in that it requires coordination to manage the constant volatility of global hydrogen supply. This includes constantly releasing reserves and replenishing them. This is a daunting task. This is a rare example of energy-importing countries working together. It will be difficult to coordinate between them in a time of tension between China and the West. They will need to place greater geopolitical tensions on one side.